I’m going to focus on RabbitMQ & Celery, what it buys you and why and when to use it. Eric’s blog always seems to be a couple months ahead of mine, so instead of re-hashing what he wrote, I’ll let you read his blog and then come back and finish my complimentary post. Go there now. I’ll wait.

Here’s the mini-rehash for those who didn’t actually go read it. Basically, RabbitMQ is a general purpose messaging queue system based on the AMQP protocol. When you need something to get executed, you simply queue up a message with RabbitMQ. It won’t get lost if Rabbit restarts, you can be pretty confident that your tasks will eventually get executed or you’ll be able to find out why they didn’t. Celery (and django-celery) is a Python library for queuing up tasks to be executed and for actually executing these tasks asynchronously. It gets its tasks from RabbitMQ although it does work with other queues as well.

Why RabbitMQ & Celery?

Not everyone needs to execute asynchronous tasks. If you’re reading this and asking yourself “why would I ever need that,” you probably don’t need it. My project involves data analysis that takes minutes for each item in the database. In addition, I periodically re-analyze items in the database. At first, I built a cronjob (using Django management commands) which would wake up and check for new items queued in the database every minute. Then, I built a second cronjob for re-analysis. As the system grew, this became hokey and had issues anytime the database crashed during this analysis. Anytime your Django view connects to some external service that may or may not be up (source control, web services) or may take a while (shell commands, massive database queries, etc.), it’s probably best done asynchronously. It’s also great for anything that needs to be executed periodically at a particular interval (caching, expensive calculations). Celery also provides built-in ways to retry failed tasks a specified number of times at a specified interval which is particularly useful for ensuring that things actually get done.

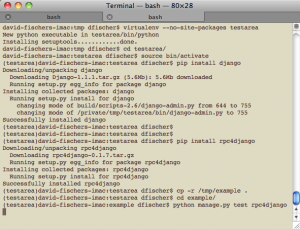

Setup & integration with Django

My Django views didn’t change much after I switched to Celery. Instead of adding an item to the database when I want to queue up an item for analysis, I simply queue up the execution of a @task with django-celery. The particular tasks that your application can handle are simply placed in a tasks.py file in your Django applications. To process the tasks, you simply run python manage.py celeryd. It can also be setup to run at boot time using init.d (Ubuntu/Debian, Redhat/Fedora). Celeryd clients can connect to Rabbit from the same server as RabbitMQ or a different server or servers in order to distribute the load.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

##old views.py def queue_task(request, data): """ A cronjob will poll for new queued items periodically and process them """ item = NewQueueItem(data) item.save() render_to_response('success.html') ## new views.py from tasks import process_item def queue_task(request, data): process_item.delay(data) render_to_response('success.html') ## tasks.py from celery.decorators import task @task(max_retries=3, default_retry_delay=5*60) def process_item(data, **kwargs): ... |

The nitty gritty

One useful bit that I had to dig to find in the Celery documentation was on locking a particular task so that two different workers don’t work on the same thing at the same time. This could happen in my application if two users queued up analysis on the same item for example. The trick is to use Django’s cache framework and lock a particular item in the cache.

A word on Djangocon

Unlike last year, I convinced work to send me to Djangocon in Portland next week. I’ll probably do some live blogging on some of the interesting topics. If you’ll also be there, say hi!